What Congress and the American People Should Be Asking About Venezuela

In Collaboration with Michael L. Burgoyne and Albert “Jim” Marckwardt

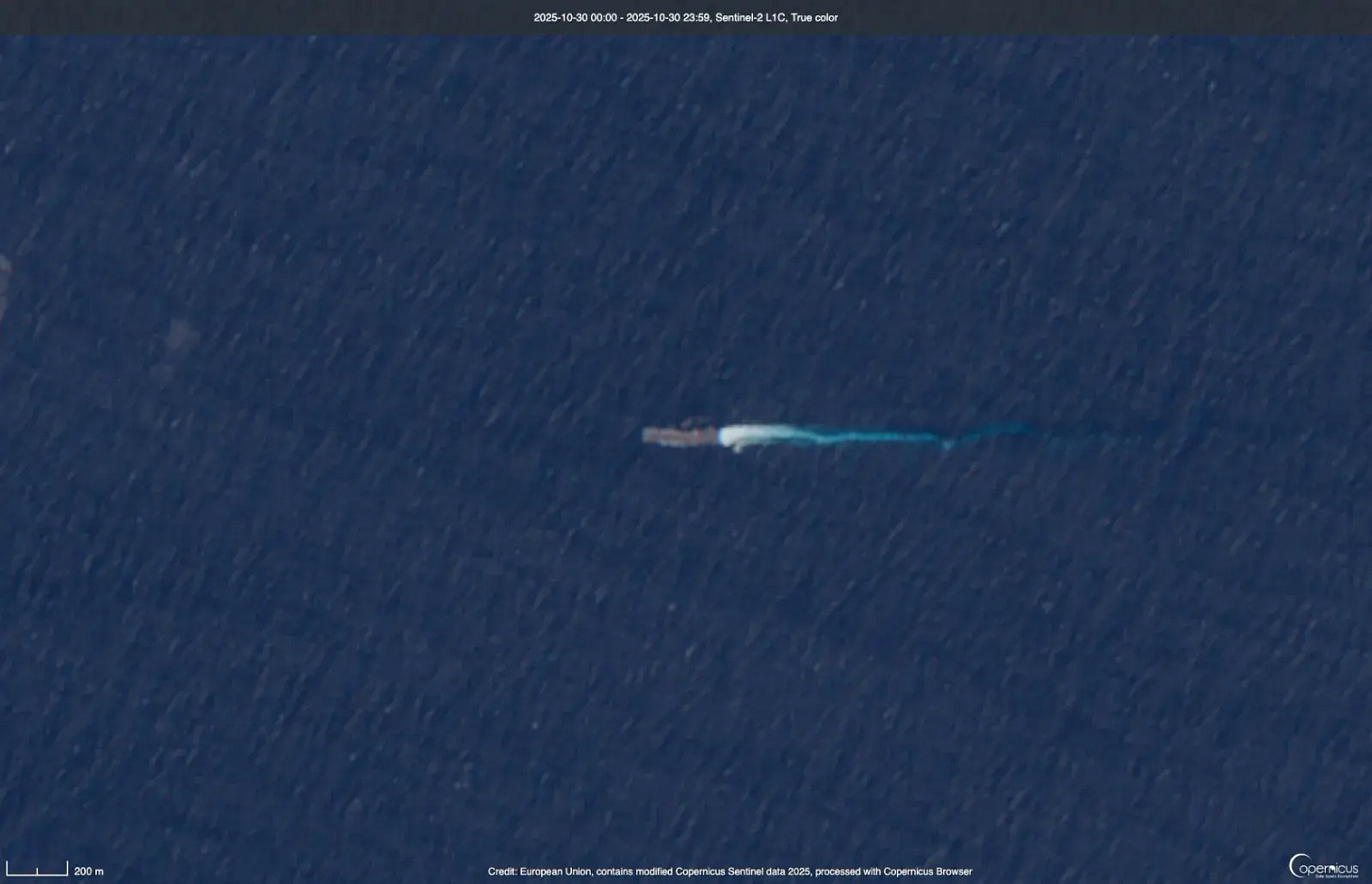

Satellite imagery captured by the European Space Agency of the USS Iwo Jima maneuvering in the eastern Caribbean Sea. Source article linked here.

It is difficult to judge the current U.S. strategy in the Western Hemisphere and its overall effectiveness as there are more questions than answers. As of this writing, the United States has amassed a substantial military presence in the Caribbean including an Amphibious Ready Group, a Carrier Strike Group, F35s, M-Q9 “Reaper” UAVs, and special operations forces. The military has conducted more than ten lethal strikes against alleged drug boats in international waters resulting in the deaths of more than 50 people. All of these actions have been conducted without an authorization of force from Congress and barring such an authorization, their continuation after November 3rd will be in violation of the 60 day limit imposed by the War Powers Resolution. If the Trump administration plans on continuing lethal strikes against drug traffickers or e…